…After the Long Good-bye

“My vigil ended this evening at 7:15pm. After an heroic fight against an unruly disease, my father has passed, and there is a hole in my heart. I want to thank everyone for the kind words of support over the past few weeks. I am fortunate to have so many friends. I will be posting information on the services just as soon as we have them. The wake will be held at my studio.”

Anyone who has been following my blog will by now have noticed the span of time that has passed between this and my last post. Some of you who follow my posts on Facebook already know the reason for this, but for the rest, I would like to explain that on December 8th, my father died of cancer. The months leading up to that time was greatly stressful, and when his illness took a turn for the worse, everything stopped. Since then, my life has been greatly distracted by the aftermath, organizing his memorial service, making decisions about his funeral, handling matters at the house, and generally trying not to think about it during the holidays that immediately followed.

As I try to get back into the swing of things, I have found that I have become motivationally challenged, in part, I know because I am still grieving the loss of my father and in part because I am still very angry about the circumstances that led to his death. So I intend, here, to tell the story and in doing so, perhaps finally let go of this grief.

First, I’ll say that my father was a smoker for many years. Most people who knew him remember him holding a pipe, which he smoked for more than 35 years. He did make the decision about 10 years ago to quit smoking, and had been completely smoke-free for the last 6 years of his life. Although he did not exercise in a regular way, he was fit, ate well and took many supplements to keep himself healthy. We never expected my mother to outlive my father, given her poor physical condition, diabetes, and emotional problems. My father was always more stable, and although he was getting older, we never expected him to get so sick, so quickly.

First, I’ll say that my father was a smoker for many years. Most people who knew him remember him holding a pipe, which he smoked for more than 35 years. He did make the decision about 10 years ago to quit smoking, and had been completely smoke-free for the last 6 years of his life. Although he did not exercise in a regular way, he was fit, ate well and took many supplements to keep himself healthy. We never expected my mother to outlive my father, given her poor physical condition, diabetes, and emotional problems. My father was always more stable, and although he was getting older, we never expected him to get so sick, so quickly.

Last June, my father began to notice pain while urinating, followed by discolored urine. This turned out to be blood, from clotting or bleeding. He went to the family practitioner, to get checked out, a man by the name of Konrad Krwaczyk. This doctor decided rather quickly that my father’s symptoms were simply kidney stones. After running some tests, my father was told that it was nothing serious.

Had my father been told it was cancer at that point, he would still be alive today. Had he gotten the infected kidney removed before it had metastasized, he would have had a fighting chance at recovery. Instead, because the official diagnosis took so long, and the treatment was so delayed, by the time we began his treatment, the only remaining option was to make him comfortable as he died.

My father went back to Dr. Konrad Krawczyk several weeks later when his symptoms returned. Dr. Krawczyk referred him to a Urologist who had a similar expectation, and ultimately told my father that the symptoms were consistent with kidney stones. Finally, after more symptoms, my father opted to get a third opinion from a Dr. Brett Lavan. Dr. Lavan ordered a CT scan and an MRI and called my father back when the results came back two days later. This was just before Halloween. Dr. Lavan said, we see some areas of concern in the lungs and the kidneys, I think it’s time to get you admitted. He arranged it so my father could be admitted that night, and so began his battle with cancer. It was his belief that by having him admitted, we could fast-track his testing and diagnosis.

The first operation they did was to take a needle biopsy of his lungs, in order to identify what type of cancer this was, which in turn, would indicate the best course of treatment. The initial biopsies came back inconclusive, so they opted to do a wedge resection of his lungs. This meant surgery to remove a larger sample which would include some of the nodules in his lungs in the area affected, and was to be sent out to California for DNA testing. This procedure also required that he be fitted with a chest tube, to drain excess blood after the surgery, something that made it very difficult for him to rest. They also did a scan of his brain, and found that there was a spot near a motor-control area that was beginning to affect his left arm. They decided that they would treat that spot with focused radiation, using the Cyberknife surgery that the hospital specialized in. After a week or so, they finally managed to release him from the hospital, allowing us to wait for news from California. Our appointments for the Cyberknife were scheduled for the upcoming week.

The first operation they did was to take a needle biopsy of his lungs, in order to identify what type of cancer this was, which in turn, would indicate the best course of treatment. The initial biopsies came back inconclusive, so they opted to do a wedge resection of his lungs. This meant surgery to remove a larger sample which would include some of the nodules in his lungs in the area affected, and was to be sent out to California for DNA testing. This procedure also required that he be fitted with a chest tube, to drain excess blood after the surgery, something that made it very difficult for him to rest. They also did a scan of his brain, and found that there was a spot near a motor-control area that was beginning to affect his left arm. They decided that they would treat that spot with focused radiation, using the Cyberknife surgery that the hospital specialized in. After a week or so, they finally managed to release him from the hospital, allowing us to wait for news from California. Our appointments for the Cyberknife were scheduled for the upcoming week.

We did our best to make Dad comfortable at home, but he was beginning to have more and more difficulty. He had by now lost complete use of his left hand, and was only slightly able to raise his left arm. The following Monday, I took my father to the hospital for an appointment to be fitted for a mask for the Cyberknife procedure. In the course of that day’s events, he met a man by the name of Henry Sadowski, who taught him a few things about being a survivor. Mr. Sadowski was fighting his second bought of lung cancer, which had spread to the brain. His attitude impressed upon my father the need to be positive and not despair.

We did our best to make Dad comfortable at home, but he was beginning to have more and more difficulty. He had by now lost complete use of his left hand, and was only slightly able to raise his left arm. The following Monday, I took my father to the hospital for an appointment to be fitted for a mask for the Cyberknife procedure. In the course of that day’s events, he met a man by the name of Henry Sadowski, who taught him a few things about being a survivor. Mr. Sadowski was fighting his second bought of lung cancer, which had spread to the brain. His attitude impressed upon my father the need to be positive and not despair.

The Cyberknife procedure was originally due for that Friday, but after seeing the latest scans, the doctors decided to move it up to Wednesday, as the spot in his brain was getting larger. On Wednesday he underwent the procedure and came home that afternoon. The Cyberknife is essentially a robotic arm that contains a particle accelerator, which moves over and around the patient in order to send overlapping streams of low level radiation to a single area of the brain from many different angles. This allows doctors to work on areas that were previously inoperable, in a manner that is not as invasive as open cranial surgery. Further, since the machine operates from many different angles, only the targeted areas get the full dose of radiation. This makes the procedure greatly preferred to whole-brain radiation treatments, which can have greater side effects.

The Cyberknife procedure was originally due for that Friday, but after seeing the latest scans, the doctors decided to move it up to Wednesday, as the spot in his brain was getting larger. On Wednesday he underwent the procedure and came home that afternoon. The Cyberknife is essentially a robotic arm that contains a particle accelerator, which moves over and around the patient in order to send overlapping streams of low level radiation to a single area of the brain from many different angles. This allows doctors to work on areas that were previously inoperable, in a manner that is not as invasive as open cranial surgery. Further, since the machine operates from many different angles, only the targeted areas get the full dose of radiation. This makes the procedure greatly preferred to whole-brain radiation treatments, which can have greater side effects.

After his procedure, our family ate at Olive Garden, perhaps our last meal out together before the end. Over the next few days, my father began to have problems with severe abdominal pain due to constipation, a condition which is not uncommon in cancer patients who are given the same drugs (Tylenol with codeine being the chief culprit). This was to be an ongoing problem throughout his treatment.

After his procedure, our family ate at Olive Garden, perhaps our last meal out together before the end. Over the next few days, my father began to have problems with severe abdominal pain due to constipation, a condition which is not uncommon in cancer patients who are given the same drugs (Tylenol with codeine being the chief culprit). This was to be an ongoing problem throughout his treatment.

We had scheduled an appointment for the following Monday in Madison at the school of Oncology and Hematology, to speak with specialists and Oncologists, who would review the data gathered to date, and offer a second opinion on a course of treatment. This was to be followed by an appointment with his Oncologist the next afternoon to determine treatment. At this point, the diagnosis was still uncertain. The weekend prior to this appointment was very rough, my father began to have difficulty standing for any length of time, was very weak, unstable in walking, and was losing his appetite. He was also getting to be restless when he would try to sleep. Most concerning, however was his shortness of breath.

I brought my massage table to the house, and worked on my father’s back, hoping to ease some of the tension we could see there. This seemed to help his breathing somewhat. We also kept him drinking water and Pedialyte to help him stay hydreated, and Ensure to help him keep his weight up. My sister and I prepared for the next day’s trip.

I brought my massage table to the house, and worked on my father’s back, hoping to ease some of the tension we could see there. This seemed to help his breathing somewhat. We also kept him drinking water and Pedialyte to help him stay hydreated, and Ensure to help him keep his weight up. My sister and I prepared for the next day’s trip.

We drove to Madison the next day, reliving a few stories on the way. The trip up there was uneventful. After reviewing the data, all the CT scans and MRI’s, X-rays and blood tests, all the doctors’ notes, the Oncologist we spoke to finally said that it was behaving like Kidney Cancer, specifically renal cell carcinoma, and so they would begin to treat it as such. By this point, the cancer had metastasized, and had spread to his brain, lungs, one whole kidney, as well as spots on his back, arms and under his chin.

I should say at this point that my sister is a nurse, an RN, who has worked in an ICU unit for many years. She had a good deal of insight into the course of treatment and the likely prognosis. Which didn’t make things easier for us, by the way.

The Oncologist in Madison said that there were three choices with regards to treatment, and they could all be very expensive. The treatment they thought would work best was designed to attack the cancer’s ability to hijack bloodflow to feed itself and further metastasize. He also said that there was no known cure for this disease, and that once it had metastasized, the majority of treatments were designed to prolong their life, rather than cure the disease.

The Oncologist in Madison said that there were three choices with regards to treatment, and they could all be very expensive. The treatment they thought would work best was designed to attack the cancer’s ability to hijack bloodflow to feed itself and further metastasize. He also said that there was no known cure for this disease, and that once it had metastasized, the majority of treatments were designed to prolong their life, rather than cure the disease.

After the meeting, we stopped to eat at Noodles in Madison. The ride home was more difficult, as we hit rush hour traffic both in Madison and when we got back to Milwaukee. By then my father was greatly uncomfortable, with back and abdominal pain, but also with exhaustion, the trip took a lot out of him. When we got him home, he settled in to rest for the meeting with the Oncologist the following afternoon.

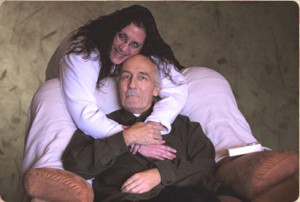

The next morning, things were not looking good. My father was pale, barely ambulatory, and having a great deal of difficulty breathing. The picture to the left is the last picture ever taken of my father, one of several taken that morning, just before we left for the hospital. You can see the fear we both shared, just how pale he had become.

The next morning, things were not looking good. My father was pale, barely ambulatory, and having a great deal of difficulty breathing. The picture to the left is the last picture ever taken of my father, one of several taken that morning, just before we left for the hospital. You can see the fear we both shared, just how pale he had become.

My sister began to think that he was anemic, which would indicate that he was bleeding somewhere, or losing blood to the tumors. His lungs were clear, but his capacity for breath was greatly reduced. Movements as simple as sitting up from a reclining position would require a few minutes to catch his breath. His breathing was very shallow and labored. We managed however to get him into the vehicle and to the hospital for the meeting with the Oncologist.

My father was greatly appreciative of his Oncologist, a woman by the name of Dr. Qamar. She was compassionate, and took action quickly, but was very straightforward in describing his condition and the likely outcome. She noticed how pale he was and concurred with my sister’s observation, ordering some blood tests which determined that he was indeed anemic.

My father was greatly appreciative of his Oncologist, a woman by the name of Dr. Qamar. She was compassionate, and took action quickly, but was very straightforward in describing his condition and the likely outcome. She noticed how pale he was and concurred with my sister’s observation, ordering some blood tests which determined that he was indeed anemic.

The social worker for the Oncology Alliance began to write up the paperwork to get the drug that would treat my father’s cancer. Because this was an oral drug, it would cost upwards of $4000 per month, none of which was covered by my father’s Medicare. The social worker began to look into ways to get the drug cheaper or possibly free, through programs sponsored by the drug manufacturers. We decided to pay out of pocket for the first week’s treatment, and see if we could qualify for the program in the mean time.

Meanwhile, Dr. Qamar suggested that we admit my father as a patient so they could get him some units of blood and do further tests. They got him a room a few hours later, and he settled in for the night.

After meeting an obligation that evening, I returned to the hospital at around 11pm that night, and saw that my father was hooked up to oxygen, to ease his breathing. Our family was there with him, and they had yet to get him a blood transfusion. Shortly after I got there, he had to use the restroom, for which he got off the oxygen. When he returned to his chair (being more comfortable sitting than reclining), he had an episode where he collapsed, his head lolled and became unresponsive. I was standing right next to him with my sister near by, she and I held him as we called for help and tried to get him to come back around.

After meeting an obligation that evening, I returned to the hospital at around 11pm that night, and saw that my father was hooked up to oxygen, to ease his breathing. Our family was there with him, and they had yet to get him a blood transfusion. Shortly after I got there, he had to use the restroom, for which he got off the oxygen. When he returned to his chair (being more comfortable sitting than reclining), he had an episode where he collapsed, his head lolled and became unresponsive. I was standing right next to him with my sister near by, she and I held him as we called for help and tried to get him to come back around.

Within a couple of minutes, he came back around, and was disoriented, but could answer questions. The late nurses felt he had a Vagal response to a bowel movement, but my sister knew it was something else, as the amount of time after made that unlikely. We managed to get the nurses to pay closer attention to his heart rate, which during the episode dropped from an average of 95bpm down to 60 bpm. I decided to spend that night with him at the hospital, what was to be the first of many.

At around 2am or so, the night nurse finally got him set up with an IV transfusion. They delivered two units of blood very slowly, each taking around 4-5 hours to complete. During this time his rest was interrupted every 15-30 minutes for blood tests, adjustments to the IV, and introductions by the new nurses, doctors, and nurses assistants as they came on duty. This type of schedule was to be the routine, unfortunately.

At around 5am, the lung doctor came in and discussed my father’s condition. He said that it looked as though he may have some fluid building up around his lungs. They wanted to go in with a scope to drain it and see where it was coming from. They scheduled the surgery for the following late morning.

At around 5am, the lung doctor came in and discussed my father’s condition. He said that it looked as though he may have some fluid building up around his lungs. They wanted to go in with a scope to drain it and see where it was coming from. They scheduled the surgery for the following late morning.

After the operation, the thoracic surgeon who performed the procedure came out of surgery to tell us that he had removed 3 liters of blood from my father’s chest cavity. (Visualize the weight of 1 and a half 2 liter bottles of soda) He should have died the night before. The surgeon said that they drained the blood and cleaned him up as best they could, his lung re-inflated nicely, but that there was a lot of raw tissue and they could not find where he was bleeding from. They left him with two chest tubes to help drain any additional bleeding. These were to be in for a few days, but ultimately remained for the better part of a week.

During that week, my father became largely exhausted. They had moved him to another (thankfully larger) room after his operation. It was very difficult to get the nurses and doctors to give him more than 2 hours of undisturbed rest at any given time. Introductions from 2-3 staff members each shift, interruptions by the nutrition aides who handled the daily menus, introductions by the many many doctors who worked with him, or covered for those who were out due to the Thanksgiving holiday, blood tests, vitals checks, assistants delivering his medication, housekeeping coming in to clean the room, remove the trash or change the linens. Add to that his physical discomfort, not being able to use his left arm, and you can see how he got very little rest during this time.

During this week, he was fitted with a pic-line, which allowed the nurses to stop poking new holes in his arms and hands when they took blood or delivered medication. His calves were wrapped with an air-driven device designed to stimulate circulation. They put an alternating pressure air mattress under him to reduce the likelihood of bedsores. The medication he was taking included morphine, vicadin, and eventually larazopan and ambien to help him sleep.

The doctors decided he was past the point where the original medication would do any good, coupled with the new spots they found in his brain, they decided to begin a course of whole brain radiation treatments. This took place each morning for about 5 days.

To complicate matters, my father was also still anemic. He went through 6-8 units of blood over this period of time, which would help for a time, but his hemoglobin levels would eventually drop. His urine was greatly discolored, at times very red. Further, since the blood they were giving him was mostly water, he began to have chronically low sodium levels, which put his heart at risk. The Nephrologist started him on a fluid-restriction diet, limiting the amount of water or juices he could take in each day, in order to correct this. Meanwhile the gestapo schedule of interruptions continued.

Finally, the worst night came. Again I was spending the night, my siblings and I took shifts to make sure someone was there, and to make sure there were no mistakes by the staff (there had already been a few). We did our best to make sure his rest was undisturbed as well.

That night, I found that my father was exceptionally restless, and was beginning to not make sense. When he had to stand, to use the commode, I noticed that his left foot was lagging and not aligned properly. When the nurse had him lift his foot, it did not lift as high as his right. Early in the morning, an observant nurse also noticed that he was showing signs of neglect in his gaze, he wouldn’t focus to his right. During this time my first thought was that he was having a stroke. We later found that the radiation treatments weren’t working, and the tumors in his brain were growing larger, further interfering with his motor control.

The next day my sister and I spoke with the Oncologist and discussed the best course of action. We knew our father was miserably uncomfortable. The doctor agreed that his being in the hospital was only going to further exhaust him. The decision was made to remove the chest tubes and shift to hospice care. We decided that it would be easier to bring my father home to my sister’s house, where everything was on one level, than to bring him to his house, where the stairs would be prohibitive.

We brought my father home on a Saturday. That night we had beer and sushi, followed by ice cream. We sat him in front of the television in his comfy recliner, which we had brought over from the house. The Hospice service had delivered a great deal of supplies the day before, including a hospital bed, a wheeled table, a walker, wheel chair, oxygen units, and medication both for his treatment and for the end. We had a room set up for him and tried to make him as comfortable as possible. That night and the next day were the last times he was really with it, the disease progressed quickly after that.

Monday night was difficult, I spent the night there with my brother, allowing my sister a chance to rest. He was becoming increasingly incoherent during this time, waking up every 20 minutes or so, asking to be adjusted in his chair. By Tuesday late afternoon he was largely unresponsive. His breathing was very labored, not having the strength to clear his throat, he could not clear his secretions, his eyes were half-lidded as he stared vacantly at the ceiling. This was one of the most difficult things I have ever experienced.

I was in the room when my father died, I saw his breathing had stopped and called for my sister, while I checked his pulse. Death can be an enemy, but it can also be a mercy. We were all glad that it was over for him, the pain and discomfort, the fear and anxiety, it was done. We called the funeral home and the hospice service. The nurse came in and prepared him for transport. The funeral service came shortly afterward and took him to be cremated, per his request.

My father died in the midst of a heavy snow storm at 7:30pm on December 8, 2009.

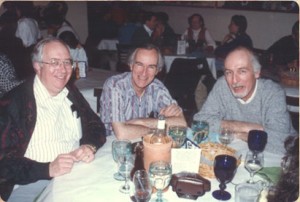

I had long ago determined that when my father died we would hold the memorial service at my studio. We did this a little over a week later. It took a great deal of time and energy to send out the invitations, post notice in the papers, contact people via phone, email, etc. The memorial service went the way he wanted it to, lots of pictures to look at, food and booze, friends and family. Overall I believe more than 250 people showed up to pay their respects, a few important ones spoke about his life and his influence on theirs.

The following Monday we held a military funeral for my father in Union Grove, WI. My father was in the Air Force, stationed in Japan during the Viet Nam war. He asked to be cremated and buried in a plot overlooking his brother’s grave at this cemetery. Again, there was a large turnout, nearly 50 people came out to brave one of the coldest days of the year.

Several days later came Christmas, then New Years. A flurry of days went by with great difficulty. We slowly began to pick up the pieces and try to get back to some sense of normalcy. There is still a great void in our lives right now.

I greatly miss my father. There are a tremendous number of things I wish I had the chance to ask him. Instead, the only thing I can really do is pass on the things he taught me to my students and family.

There are probably a great many moments that I am omitting from this record, some out of respect for their significance, some because they are too painful to repeat. Over the next week I will be posting artwork that I did during this time, artwork I was able to share with my father when he was in the hospital.

In hindsight, there were a ridiculous number of problems with the treatment my father received (or didn’t). I am very angry with the process, and why everything needed to take so long. I feel as though that was time, crucial opportunity wasted. The endless interruptions alone could make anyone sick, compounded by stupid mistakes and a lack of coordination made this process extremely frustrating. The number of doctors (over 20 at last count) involved made things much more difficult to get answers, and further exhausted my father as every doctor, nurse, nurse practitioner, assistant and lab tech had to ask him the same damn questions.

I know that a lot of this is procedural, there for redundancy and also to cover liabilities, but I knew then that there has to be a better way to treat people who are sick than this. And…I was right. Please visit this site today: http://www.huntsmancancer.org. I first heard about this on the Glenn Beck program on Fox News Channel. The system they describe is night and day to what we experienced. I wish, I truly wish we had been able to get my father there for treatment, it could have made a world of difference.

That being said, my father wanted a tribute to be made to two doctors in particular: Dr. Rubina Qamar and Dr. Brett Lavan, both of whom went out of their way to insure that my father received the best treatment available. Dr. Qamar came in very early on Thanksgiving day during her scheduled vacation time to check on my father. Dr. Lavan had the clarity to identify my father’s condition as cancer, and to expedite the process of getting him treatment, when others would not. You two are both a credit to your profession.

That being said, my father wanted a tribute to be made to two doctors in particular: Dr. Rubina Qamar and Dr. Brett Lavan, both of whom went out of their way to insure that my father received the best treatment available. Dr. Qamar came in very early on Thanksgiving day during her scheduled vacation time to check on my father. Dr. Lavan had the clarity to identify my father’s condition as cancer, and to expedite the process of getting him treatment, when others would not. You two are both a credit to your profession.

On the other hand, I would also like to publicly identify Dr. Konrad Krawczyk as the person who missed my father’s diagnosis, and cost him time that could have saved his life. I would encourage everyone who reads this to avoid his practice, and recommend the same to others.

Sage Arts Studio

Sage Arts Studio